Talking about Machines that Talk

Human language, intelligence, and mind are fundamentally intertwined with our embodied being-in-the-world.

Last weekend, I returned to the uncanny little town of Bombay Beach, CA. While there I presented more of my recent work on philosophy and AI. Specifically, I gave a variation on my talk "Frictionless Spinning in the Void: AI is not 'There'."

The context was a singularly inspiring arts and philosophy event called Convivium, put on by the Bombay Beach Institute, an organization co-founded by Tao Ruspoli (who had me on his podcast during my last visit and who directed the excellent philosophical documentary Being in the World, among others).

Just before my talk, my friend Mark Wrathall, a philosophy professor at Oxford, gave a provocative talk called "What Can I Really Want in a Technological Age?"

Readers of this site will be interested to know that Mark recently published an excellent brand new entry on Martin Heidegger for the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. This entry is now one of the best self-standing, brief introductions to Heidegger's thought that is available anywhere. Check it out.

"Frictionless Spinning in the Void"

The point of the talk I gave at Convivium is to open up questions and inspire some wonder around what it means to "have" language, or to "be" a "linguistic" entity, in the first place.

The talk is much more about human language than it is about machines having language. I don't take a detailed stand on whether LLMs know language or whether they are instead something like "stochastic parrots" or "linguistic automata." They do seem to have linguistic powers that might reveal the workings of some kind of synthetic, alien mind.

(Though, ultimately, I think the real question is not whether or not LLMs have something like a mind, but how we incorporate these new linguistic tools into our practices and relationships. The action is in our coupling-with them.)

In order to understand and assess the nature of such seeming linguistic and cognitive powers, we need to first clarify what it means to say that we ourselves "have" language. We also need to clarify how our own linguistic abilities are related to our form of "mindedness," our way of having a mind.

For example, we have minds that are capable of forming beliefs about the world, and capable of forming intentions to bring about future courses of action in the world. Our beliefs can be true or false. We can linguistically express them in our assertions. Our intentions can be fulfilled or unfulfilled. We can linguistically express them in our promises.

Technically speaking, LLMs cannot do any of this. They generate strings of text according to statistical regularities. But they have no relationship to the truth, and no intentions or purposes of their own. Their linguistic powers come alive only in their dance with us, their users. We supply the meaning, the purpose, the concern for truth.

Even so, the sometimes dazzling outputs of LLMs tempts many intelligent people to suppose that our own linguistic capacities are really just like what the LLMs are doing.

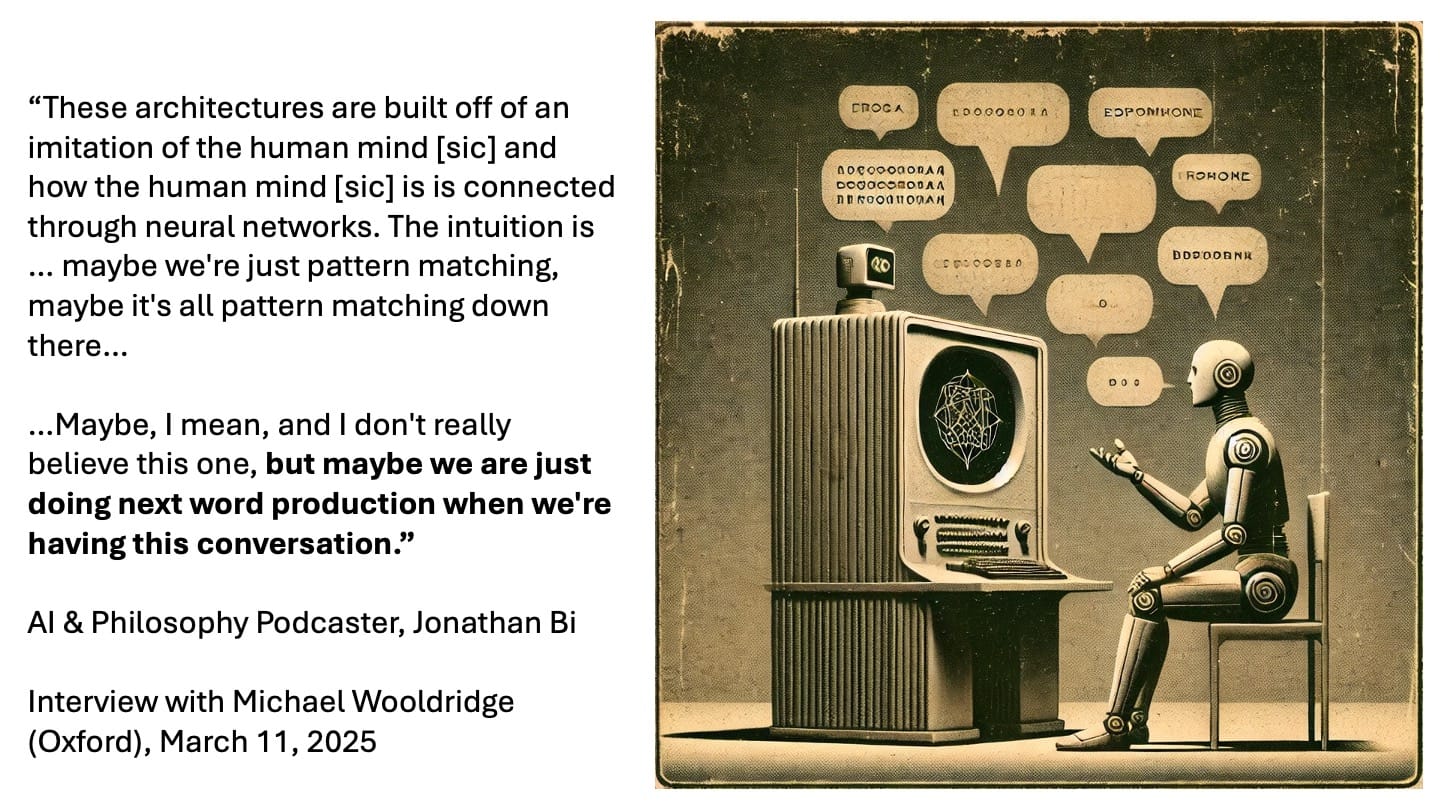

For example, see what the thoughtful philosophy and AI blogger Johnathan Bi says here in his recent, awesome, interview with Michael Wooldridge of Oxford, author of The Road to Conscious Machines: The Story of AI:

You can watch the clip of this stretch of the conversation between Bi and Wooldridge here. While you are at it, subscribe to Bi's YouTube channel and Substack.

Of course, Bi here rightly qualifies the claim that human language is itself just a matter next token prediction (one way to describe how LLMs generate text). He seems tempted by this identification, but he is certainly not endorsing it here. I think the reason he bothers to entertain this highly reductive interpretation of human language as mere "predictive pattern matching" is because, as he surely knows, this is exactly the intuition that many contemporary enthusiasts and casual observers of AI are strongly tempted to believe.

Bi's introduction of this overtly reductive view of human language into the conversation also reflects his astute skills as a philosophical interviewer. This proposal sets up Wooldridge for one of the most striking and powerful stretches of their conversation.

In the quotation from Jonathan Bi in the slide image above, I draw attention to another common misnomer that demands our caution. Bi remarks that the "architectures [of LLMs] are built off an imitation of the human mind and how the mind is connected through neural networks." But what he should have said, and I what I believe he really meant to say, is that LLMs are built off an imitation of the human brain and its connectivity through neural networks.

My friends, the mind is not the same thing as the brain!

- Our brain is this wondrous and mysterious bulbous material mass contained inside our skulls and often described as the most complex object in the known universe. By current estimates it has about 86 billion neurons and 100 trillion synaptic connections.

- Our mind is a set of capacities for acting in, relating to, learning about, knowing about, talking about, and making sense of the world. Our mind certainly depends on our brain, but they are different things! Indeed they are different kinds of things with different ontological structures.

Arguably, the emergence (and actualization) of our mind's capacities requires a certain style of embodied, cooperative, caring social relations that, in turn, enable the emergence of language. Many traditions in philosophy and social science, including the tradition of Heideggerian phenomenology, converge on this point though it is, of course, contested.

It is common for AI researchers and cognitive scientists to hold a disembodied view of the mind. I encounter this view frequently when I attend AI-and-philosophy related events in the Bay Area. In the following clip, at an event put on by two AI researchers whom I deeply respect (Joscha Bach and Jeremy Nixon), you will hear my disembodied (off-screen) voice, ask a question about the plausibility of disembodied consciousness:

Clip of an exchange I had with the AI researchers Joscha Bach (left) and Jeremy Nixon (right) about the plausibility of disembodied minds.

I can't go into further details here, but in my "Frictionless Spinning in the Void" talk, I argue that our linguistic and cognitive abilities are fundamentally intertwined with and dependent upon what Heidegger calls our "being-in-the-world": our direct, embodied immersion in and familiarity with our everyday world.

LLMs, though, have no primordial embodied presence in the world. Their striking linguistic capacities emerge from their ability to statistically model patterns and associations across vast corpora of written text. But as such they are a "frictionless spinning in the void": their linguistic abilities are oriented to finding and generating coherence in bodies of text; thus they spin free from any presence in, contact with, or concern for the world. They are "worldless," to use another of Heidegger's phrases.

Note: "Frictionless spinning in the void" is a phrase I got from the philosopher John McDowell. In his book Mind and World (1994), he used this phrase to criticize certain conceptions of the human mind that see it as detached from the world, operating in a self-contained conceptual space without being constrained or guided by reality. In the subtitle of my talk, "AI is not 'There'," the "there" refers to Heidegger's understanding of human existence as "Dasein": being-there. Where is there? The world. Dasein is being-in-the-world.

Language for us is not a free-floating generative capacity disconnected from our primordial embodied presence in the world amidst other people, in pursuit of projects that matter to us. There are many surprising and important corollaries and implications that follow from this basic picture, and my "Frictionless Spinning in the Void" talk explores some of them.

This is not a denigration of LLMs. They are wondrous new kinds of entities! They are ontological marvels! Ilya Sutskever, one of the most important AI researchers of our day (and of any day), has rightly captured something of this marvel when he described ChatGPT as "the most complex software object ever made." I truly believe LLMs warrant our awe and even a kind of respect. From now on, for better or worse, they will be our co-participants in the disclosure of the space of possibilities that constitutes our world.

Return of The Phenomenological Critique of AI

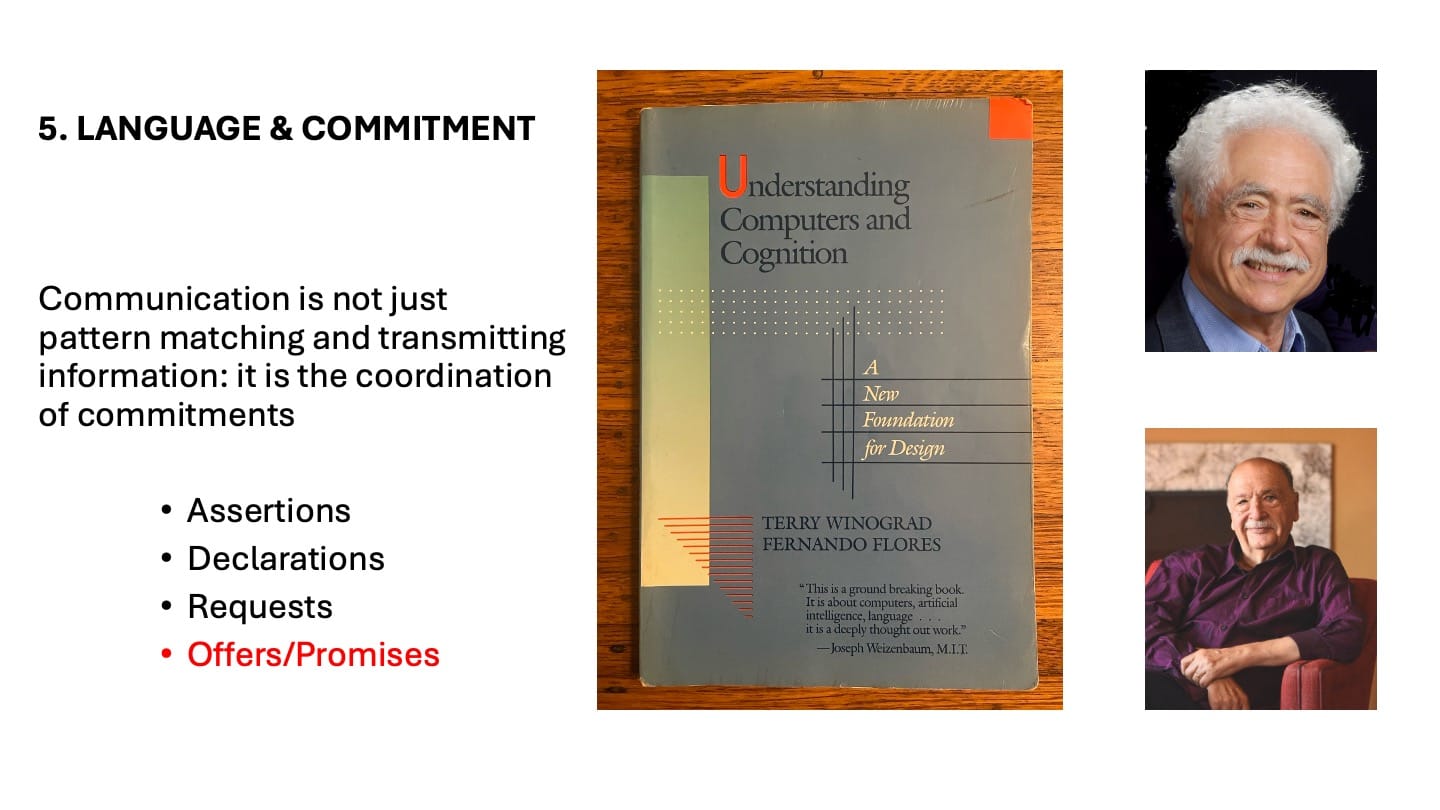

As I have mentioned several times in these pages, the arguments above belong to my contemporary rehabilitation of the phenomenological tradition of AI-critique originally launched by Hubert Dreyfus in the 1960s ("Alchemy and Artificial Intelligence," 1965) and 70s (What Computers Can't Do, 1972), and further developed in the 1980s and beyond by thinkers such as John Haugeland (Artificial Intelligence: The Very Idea, 1985), Terry Winograd & Fernando Flores (Understanding Computers and Cognition, 1986), and Bert's brother and co-author Stuart Dreyfus (Mind Over Machine, 1988, written with Bert).

The claim that human language, intelligence, and mind are fundamentally intertwined with our embodied being-in-the-world (rather than being a free floating, disembodied capacity to find and generate statistical patterns in text) is, in fact, articulated quite forcefully (if in slightly other terms) by Michael Wooldridge in his conversation with Johnathan Bi.

I thoroughly recommend everyone take some time to watch the closing segments of this video. This conversation, especially last 18m, is essential viewing for anyone seeking to nourish their interpretation of what's going on in AI today:

Wooldridge reveals a deep sympathy with the arguments one finds in the Heidegger-inspired, Dreyfusian tradition of AI-critique. The only reason this is a surprise is the somewhat dismissive tone Wooldridge, in The Road to Conscious Machines, takes towards Dreyfus's work.

Wooldridge agrees that the intelligence of LLMs is profoundly limited by the fact that they have no embodied presence in the world. To this I would add that there is some sense in which LLMs have a concrete relation to the world: it is through us, their embodied designers and users.

I think this shows that the right unit of analysis for thinking about the intelligence and abilities of LLMs is not the machine in and of itself: it is the coupling of human and machine. What new worlds and possibilities can we open up together? What possibilities and worlds are shutting down?

Revisiting Understanding Computers and Cognition

The idea that we should be thinking about what humans and computers can do together rather than thinking about what computers can or cannot do for themselves is precisely one of the main messages of Understanding Computers and Cognition, by Terry Winograd and Fernando Flores, two longtime mentors, collaborators, and thinking partners of mine.

I recently attended a talk Terry gave at the Berkeley Institute of Design (BiD) about the history and contemporary relevance of Understanding Computers and Cognition.

A useful commentary on Terry's BiD talk is presented in this blog post, "Reflections on What Computers Can (And Still Can’t) Do," by Stef Hutka.

For a recent, stimulating interview with Terry o these questions, see "LLM has a representation of care, it doesn't care, An interview with Terry Winograd by Harry Halpin."

Harry Halpin himself, founder of the cutting-edge internet privacy company Nym, is a forceful and kindred thinker on these issues. I recommend his recent paper in AI & Society, "Artificial Intelligence versus Collective Intelligence," which is available here.

Please let me know what comments, questions, or provocations you have after reading this post!

Join the Conversation

Your support makes Without Why possible. If you upgrade to a paid subscription for as low as $8 per month you gain the opportunity to post and reply to comments on these pages, and to join a growing community of conversation here. You will also receive extra-special members-only posts. Sign up today!