Strange Familiarity, Part Two (Repost)

An overview of the Dreyfus Model of Skill Acquisition and its relevance to Heidegger's ontology.

I originally posted this piece as a members-only post back on January 13. I am reposting it today as all-access. Please check it out and let me know what you think! This was the second installment of a two-part post. You can review Part One here.

As we have seen, Heidegger is fascinated by our everyday skills, like our skills for making breakfast bleary-eyed in the morning without needing to think too much. He sees such skillfulness as an important and overlooked realm of phenomena calling for our philosophical reflection.

In Heidegger's picture, traditional philosophers, obsessed with the stance and powers of reflective, rational deliberation, relate to the world like a strangely unfamiliar kitchen. In an unfamiliar kitchen, we don't know our way around; we have to reflect and deliberate about what we see and what to do.

These philosophers generalized this stance of detached observation, covering up the realm of pre-reflective everyday skill. In this stance, the world is revealed as a bunch of present-at-hand things to behold and categorize.

But most of the time we are involved and immersed in the world, not observing it.

You can get around in your home kitchen and make your habitual breakfast without needing to deliberate about the steps of the process. This is an engagement with the realm of what Heidegger calls the ready-to-hand: knives, bread, toasters, plates, refrigerators, coffee makers, and the like.

Something is ready-to-hand if we have skills for dealing with it without having to stop and think. Heidegger claims that the world reveals itself in a distinctive way through our skillful familiarity with what is ready-to-hand. But traditional philosophers missed this completely.

There are several reasons for this forgetfulness of familiarity.

The realm of the ready-to-hand conceals itself from scrutiny. Philosophers scrutinize.

Skills enable us to flow in the familiar. But skills have a peculiar feature. When we are expert at a skill, we can act without thinking and deliberating about what to do. In fact, thinking about our skills too much interrupts the flow of exercising them.

The detachment of reflection clashes with the flow of the familiar.

Thrown Projection†

Heidegger's notion of the familiar "ready-to-hand" can help us think about the nature of expertise and skill.

When we learn new skills, we expand our repertoire of what is ready-to-hand. But in the process of learning new skills, we draw upon our ability to observe and scrutinize: we deliberately follow rules and instructions and pay close attention to what we are doing.

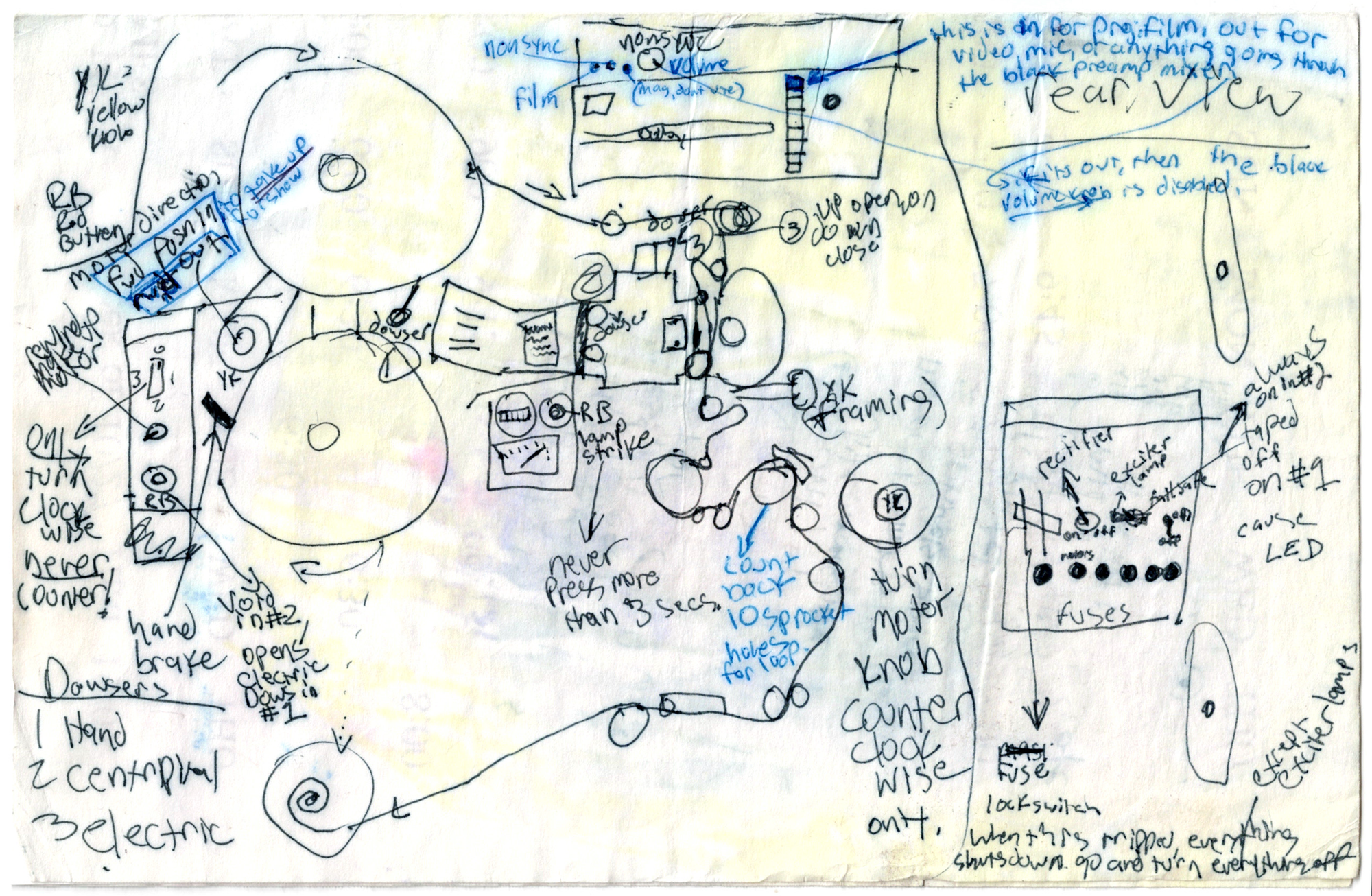

This ties to today's image: a diagram drawn not by a child, but by a 22-year-old recent Berkeley philosophy graduate named B. Scot Rousse (that's me).

When I graduated with my Philosophy undergraduate degree, I took myself directly to my favorite movie theatre in downtown Berkeley, a homely but welcoming place called the Fine Arts Theatre (it is now a faux-art deco apartment complex with the same name).

I had worked as the projectionist for the film department of UC Berkeley for two years. My job was to show the history of cinema on 16mm film prints to the film studies classes. I fell in love with this role. As the projectionist, you are the last link between the film makers, sometimes long dead, and their audience. You enable an artwork to do its work; you help create an experience of aesthetically absorbed self-forgetting in the audience. This is a secularized sacred position.

When I presented myself at the Fine Arts Theatre, I happened to show up on a day when the head projectionist, Josephine, was there. She had strong hands, lavishly smudged with black grease. She invited me into the booth and showed me the whirring projectors and their messy, archaic carbon arc lamp houses.

Josephine was active in the projectionist's union, IATSE Local 169, and this theatre, the Fine Arts, happened to be the place where the union held its meetings. I was invited to attend the next union meeting, whereupon they welcomed me into the union as a "break in" trainee.

Even though I had experience in the projection booths at UC Berkeley with their compact 16mm machines, the 35mm booths in commercial theaters were significantly more complex. They were strangely unfamiliar kitchens.

I needed to be alert, detached, and observational as I moved through the booth and learned from the weirdly charismatic master projectionists in the union. I needed definitions, rules, and procedures to find my way around. Making diagrams like the one at the beginning of this post was part of my training.

Eventually, with enough experience, the booths and the projection equipment became ready-to-hand for me, and I was declared ready-to-work on my own. Before being declared booth-competent, one of the master projectionists, Bob, ambushed me with an impromptu trial. Bob was a gruff and reticent man with smooth, short, white hair and a perpetually sweaty brow. He was always smoking cigars in the booth.

Bob and I were sitting next to a projector that was running a movie for the audience below. He asked me what I would do if the film broke in the projector. Before I had time to answer, he took a pair of scissors and cut the film.

Experts can adapt to shifting circumstances without needing to plan everything out. I was not yet an expert in the booth, and I failed this test. But the real point of the exercise was for Bob to teach me his method for dealing quickly with a film-break, and to do so without needing to interrupt the screening. The audience below never sensed what happened.

When projectionists do their job well, no one ever knows they are there. They remain withdrawn into the background, like the film projector itself.

One of the booths where I trained had a big poster of the words SHIT HAPPENS. Experts are able to deal flexibly with the shit when it happens. They wield a vast repertoire of ready-to-hand responses to the inevitable disruptions and shifts that are bound to arise in life. Experiencing a film break in real time brought me one step closer to projectionist expertise.

Familiarity and Skills

With this background, I now want to introduce a theory of expertise and skill acquisition that expands upon Heidegger's notion of the ready-to-hand: The Dreyfus Skill Model.

The Dreyfus Skill Model was formulated by the brothers Stuart and Hubert Dreyfus in a series of papers and books starting in 1980. I am myself a co-author with Stuart on the most recent version of the Skill Model from 2021. I am also the author of the current Wikipedia page. (I talk more about all of this below).

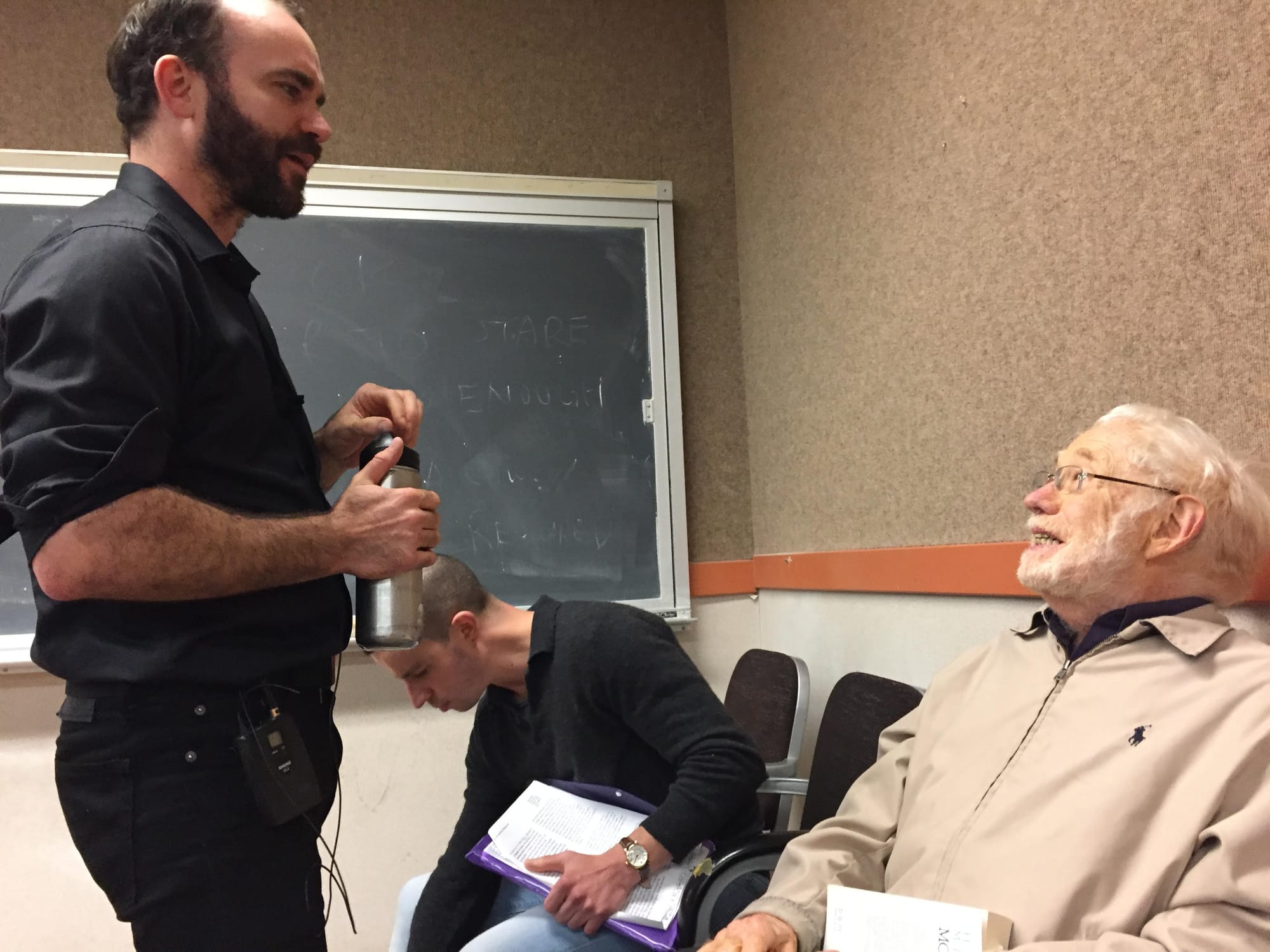

Stuart has told me that he did not have Heidegger in mind when he was originally formulating the Skill Model. Hubert saw the connection and drew upon his understanding of Heidegger when he joined with Stuart to elaborate and expand the theory. Hubert Dreyfus, who died in 2017, was one of the most important Heidegger scholars in the world.

What follows below is a revised and compressed extract of the Wikipedia entry on the Dreyfus Skill Model. As mentioned, I am the author of the current entry; it is still a work in progress! How I came to take this Wikipedia page under my protection is a story I will tell at the end of this post.

As you read this summary, pay attention to where you see Heideggerian themes such as the "ready-to-hand" or the "present-at-hand." Notice the theme of the strangely unfamiliar kitchen that, little by little, becomes a familiar zone of the ready-to-hand.

The Dreyfus Skill Model proposes that a student passes through five distinct stages of novice, advanced beginner, competence, proficiency, and expertise, with a sixth stage of mastery available for highly motivated and talented performers.

Animating the Skill Model is a common experience. In acquiring new skills, students must first rely on rules and procedures while deliberately figuring out what to do. As they gain experience and progress towards expertise, students gradually let go of the rules and procedures while gaining the ability to act fluidly, without deliberating or making decisions. The more familiarity they gain in their domain, the less they need rules and procedures, and the more they can act from their emerging intuition.

Stage 1: Novice (Beginner)

Novices rely heavily on context-free rules and step-by-step instructions. Their performance tends to be slow, clumsy, and requires conscious effort. Novices struggle to adapt when situations don't align with the instructions. A novice cook strictly follows objective recipe measurements and timing, regardless of variations in ingredients or peculiarities of the cookware.

To progress, novices need to keep gaining experience and making mistakes in a variety of situations.

Stage 2: Advanced Beginner

Advanced beginners recognize situation-specific nuances and can apply experience-based maxims beyond general rules. For instance, an advanced beginner cook might adjust heat based on the smell and look of the food as it is cooking rather than just the instructions in the recipe. They have had enough experience to recognize the smell of burning oil and can now apply the maxim that “the smell of burning oil usually means the heat is too high.”

The performance of an advanced beginner is more sophisticated than novice, but it is still analytical. Advanced beginners continue to struggle with unfamiliar situations. At the same time, they begin to feel more emotionally engaged, often becoming overwhelmed or frustrated. Progression requires building further emotional involvement and commitment to outcomes.

Stage 3: Competence

Competent performers choose specific goals and adopt an overall perspective on what their situation calls for. A competent cook can choose to have the cold dishes ready before the hot ones. Success and failure now partially depend on the performer’s choice of goal and perspective, not just on how well they follow rules. This leads to higher emotional involvement, with competent performers feeling joy or regret according to the outcomes.

While more fluid than advanced beginners, competent performers still proceed by analysis, calculation, and deliberate rule-following.

Competent performers show improved coordination and anticipation but often stick rigidly to chosen perspectives even when circumstances change. To advance to proficiency, more risks need to be taken with letting go of rules and procedures while trusting one’s emerging intuition.

Stage 4: Proficiency

Proficient performers intuitively grasp what a situation calls for but consciously decide responses. When a perspective intuitively occurs to them, proficient cooks can immediately sense a range of dishes that can be made with a collection of ingredients. However, they will still rely on the rules and procedures of recipes, and still need to appeal to procedures in order to cope with changing circumstances (missing ingredients, for example.)

The transition to expertise requires further letting go of rules and procedures while gaining more direct experience learning which intuited perspectives work in which kind of situation.

Stage 5: Expertise

Experts demonstrate seamless integration of perception and action. An expert chef creates dishes without recipes, intuitively adjusting techniques and ingredients based on specific circumstances. They can also imagine possibilities from a set of ingredients or a chosen theme without a pre-defined plan.

When circumstances abruptly change (ingredients run out, or cookware is damaged), expert chefs smoothly adapt and shift perspectives on how to proceed.

Experts often struggle to precisely explain their actions. Their expertise exceeds the bounds of neatly defined rules and procedures.

Stage 6: Mastery

Masters seek to expand and refine their repertoire of intuitive actions. In doing so, they sometimes create new possibilities of performing and transform the style of their domain.

Masters identify overlooked aspects of a practice and experiment with new approaches, accepting short-term drops in particular performances for long-term expansions in their intuition.

A most-intriguing master chef I learned about recently is Dominique Crenn, who describes her dishes as "poetic culinaria." I strongly recommend the episode of the Netflix series Chef's Table that features Crenn (Season 2, Episode 3).

A Nexus of Familiarity

Many vital threads connect me to the Dreyfus Skill Model.

Hubert Dreyfus (or "Bert" as his friends called him), was one of my PhD advisors. I came (back) to Berkeley to finish writing my dissertation on Heidegger with him, and I then worked and taught closely with him for the last eight years of his life. He was a dear friend and mentor to me. Stuart and I have become close friends and co-authors as well, especially over the past 7 or 8 years since Bert died.

Bert introduced me to Fernando Flores, an immensely important collaborator and mentor of mine over the last ten years. Both Bert and Stuart were on Fernando's committee for his 1982 doctoral dissertation at UC Berkeley, "Management and Communication in the Office of the Future," which I will write about in a future post.

In 2016, Stuart, Bert, and I co-wrote a foreword (here) to a wonderful book by my friend and colleague Gloria P. Flores (Fernando's daughter): Learning to Learn and the Navigation of Moods (see here). Gloria took up and expanded the Dreyfus Skill Model to reveal how moods play an important and overlooked role in how we learn (or fail to learn) new skills.

Stuart and I initiated a still-ongoing series of regular lunches together in 2017. We began to discuss the scholarly literature on skill acquisition and to speculate about how the Dreyfus Skill Model might need to be updated or revised in order to answer various criticisms of it that inevitably emerged.

When a weirdly acrimonious and shallow criticism of the Skill Model was included in an early issue of a brand new scholarly journal called the Journal of Expertise, Stuart and I were ready to respond. Our brief response article, concocted with an appropriate dash of scorn, was published in the subsequent issue of the journal.

Next, I was honored when Stuart asked me to co-write with him a fully-developed, updated version of the Dreyfus Skill Model for a new volume that was being prepared to celebrate its pervasive influence: Teaching and Learning for Adult Skill Acquisition: Applying the Dreyfus and Dreyfus Model in Different Fields (2021).

Our co-authored essay, "Revisiting the Six Stages of Skill Acquisition" (here) appears as the first chapter in this book.

Stuart and I were particularly concerned to update the main examples used to explain the Skill Model. He and Bert always used the examples of learning to play chess or to drive a stick-shift car. Since almost no one (in the US, anyway) learns to drive stick-shift cars anymore, we really needed to come up with an alternative example.

At the time of writing that chapter with Stuart, I was in a rigorous training to overcome my philosophers' condition of being a permanent stranger in any given kitchen. The only food I knew how to cook was frozen pizzas. My partner Alicia, an amazing cook, was acting as my mentor in the kitchen. This was the learning-experience I drew upon when I was working with Stuart to update the examples for the Skill Model.

After becoming so involved in articulating and defending the Skill Model, I realized something needed to be done about the Wikipedia page devoted to it. The previous version of the page was stilted, incomplete, and at times exuded malicious ignorance of its subject matter. I know the current version needs more work. If you have any suggestions for how to improve it, please let me know!

The Skill Model, and my relationships with Bert and Stuart, have been extremely influential upon me. You will find me writing more about them in the future.

What questions, thoughts, or perplexities does all of this bring up for you? Share in the comments!

I would love to hear from you about questions such as:

- Where do you find yourself lingering at the level of competence, and what steps could you take to move closer to expertise?

- How can you tell when you've advanced to a higher level of skill in an area that matters to you?

Footnotes:

†Thrown Projection.

In the world of cinema projection, the "throw" is the distance between the projector's lens and the screen. Presumably without having the cinema in mind, Heidegger summarized his understanding of human existence as a "thrown projection" (geworfene Entwurf).

Here "thrownness" stands for the passive dimension of human life. We are thrown into a world, and a family, and a body, and an "everything else" that we did not choose; while "projection" stands for the fact that we are, nevertheless, always cast out into the future, on the basis of this thrownness, whether we like it or not.

I couldn't help but title my 2011 PhD thesis at Northwestern University: Thrown Projection: An Interpretation and Defense of the Hermeneutic Conception of the Self in Heidegger's Being and Time.